For a draft in Dutch, click here: OTTO SELZ – Monument voor een vergeten pionier

by Richard Ridderinkhof, professor of Psychology at the University of Amsterdam and member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences

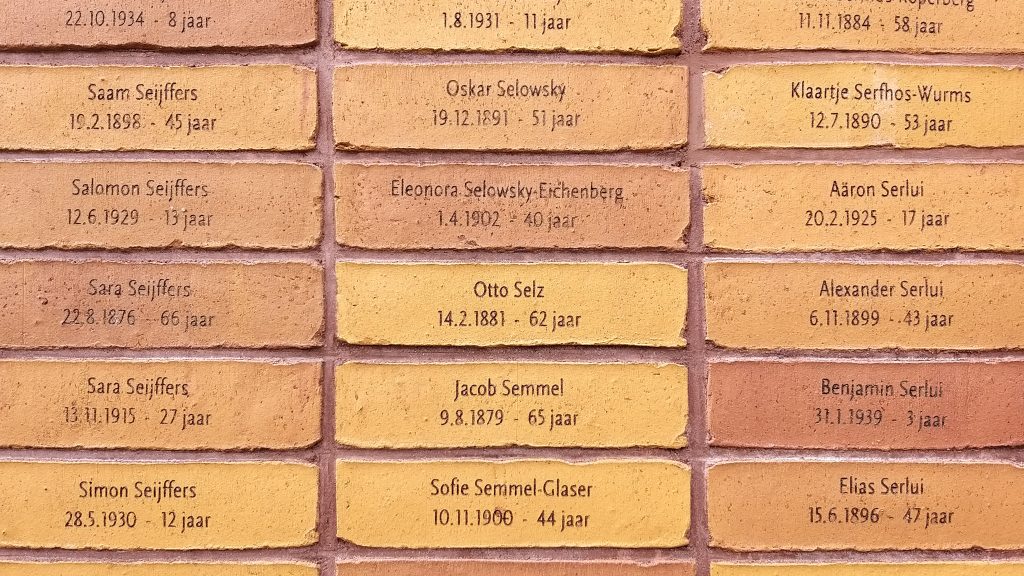

On April 21, 2022, a memorial was unveiled for Otto Selz. One may encounter this unknown name when wandering through the National Holocaust Names Monument – one hundred thousand bricks with the name of someone who was deported from the Netherlands to the Nazi camps and never returned. Selz, a now forgotten Jewish scientist, had fled from Germany to Amsterdam.

(photograph by the author)

That lost name caught my eye, about ten years ago, on the back of a book in the ramsj. Bought for 1€. Entitled Otto Selz, the book was dedicated to him in 1981 by Adriaan de Groot and Nico Frijda, Amsterdam’s most famous psychologists ever. As a child Frijda had known Selz. Over 70 years later he told me about the refugee who came to visit his parents. A friendly man who spoke German and presented him cigar bands for his collection.

The book was a tribute to this refugee, a century after his year of birth. In the book, international leaders of the cognitive sciences praised Selz as their forerunner. Nevertheless, he has remained unknown.

Last year, someone bricked up the stone of an unknown person – Otto Selz, a scientist who did not return. This year we are bringing him back. A monument to a forgotten pioneer.

Goal-directed

In the 19th century, psychologists took a big interest in purposeful action: motivation, desire, striving. Behavior that is not controlled by external stimuli but from within, driven by the will, by desires and intentions. The idea that just thinking about the intended effect of an action actually sets that action in motion was as surprising as it was obvious. Thinking about a goal (e.g., scoring a goal) provides an impetus for purposeful action (a forceful kick into the upper left corner) – and before you know it, you are already setting the appropriate movement in motion. In 1924 Selz wrote: “In games of skill, it is more effective to concentrate on the result to be achieved than on the movements to be performed, because concentration on the movement result increases efficiency.” Sports science would not discover this again until our century.

Selz applied the ideas of goal-oriented action to goal-oriented thinking. Participants in experiments reported extensively on their thought processes during questions such as “how to make sure a candle won’t leak” or “how come candles give light”. The extrinsic instruction is transformed into an inner goal; the goal, according to Selz, leads to thought schemas, which give the trajectory of thought a purposeful course. Intelligence, according to Selz, is therefore the ability to master adequate thought schemes for achieving goals. And, above all, to apply them to new, unfamiliar situations.

Selz’s thinking revolved around the workings of the mind as a ‘mechanism’, and in doing so he was far ahead of his time. His work was groundbreaking. But with the outbreak of World War I, it got sidetracked.

Selz served on the Western Front in France, but when he was wounded in 1917 he was brought to Berlin. The War Department had him study how to prevent airplane accidents. He developed detailed accident protocols, and in doing so he discovered that aircrew simply did not have any purposeful scheme of thought for emergency situations. The personnel should therefore practice with all kinds of emergency situations, so that when the occasion arose, they could quickly draw on a rich repertoire of thinking schemes: effective, goal-oriented actions. After the war, Selz was decorated with the Iron Cross, and appointed professor of psychology and pedagogy.

(Source: https://www.marchivum.de/de/stolperstein/prof-dr-otto-selz; public domain)

Selz in the Netherlands

His chair focused primarily on applied science. Selz applied his theory of goal-directed thinking to educational problems, with the aim of optimizing the level of intellectual achievement in schoolchildren. He analyzed their verbal thinking protocols, and determined what goal-directed thinking schemes they were using. He then made them aware of their thinking schemes, and of smarter alternatives. He used more advanced learners to explain and teach their thinking schemes. Careful experimental studies showed that his program actually helped children with learning problems.

This ‘paradigm of practice’ brought him much acclaim among educators in Germany and the Netherlands. However, his career came to an abrupt end when the Nazis came to power in 1933. The National Socialist Party enacted racial laws that made it impossible for Jews to practice their profession. A transfer to the prestigious University of Heidelberg failed: non-Aryans were no longer appointed. On April 4, the Jewish Selz was removed from office by decree of the Minister of Culture and Education, under the pretext of “maintaining security and order”. He was denied access to his institute and laboratory. After the events known as Kristallnacht, in November 1938, Selz was arrested and imprisoned in Konzentrationslager Dachau. Five weeks later he was released on condition that he leave the country.

He filed for emigration to the Netherlands. Not that the climate for refugees in the neighboring country was that favorable: the livelihood opportunities of the Dutch population were under pressure, and displaced refugees presented an additional economic burden. The Dutch state left aid for destitute refugees to private and religious organizations. All kinds of administrative regulations limited the opportunities for foreign scientists at Dutch universities.

Nevertheless, Selz received an invitation to come to the University of Amsterdam, thanks to the renowned pedagogue Philip Kohnstamm, and with the support of Geza Révĕsz, the founder and director of the Psychological Laboratory. Selz arrived in May 1939. He made ends meet on 60 guilders a month, provided by Jewish charities. He befriended Kohnstamm, Révĕsz, and the renowned economics professor Herman Frijda (father of little Nico).

Révĕsz involved Selz in the work of his doctoral students, offering him the opportunity to publish his work in the journal Acta Psychologica, which he had founded. Kohnstamm brought him to the ‘Nuts-seminarium for Pedagogics’, a teacher training institute of the University, where he lectured on the importance of fostering the intellectual development of children. In a seminar in April 1940 at the Rembrandt House, Selz told his audience that the successive drafts of Rembrandt’s etchings show how the artist, relentlessly corrected the defects of his original conception (redistributing, for instance, main and secondary figures) before achieving the intended effect.

Of the impending darkness, he seemed unaware.

(Source: https://www.joodsmonument.nl/nl/page/227036/herman-frijda; public domain)

Westerbork

Sometime after the German invasion in May 1940, Jews were no longer allowed to profess in public institutions, and Kohnstamm, Révĕsz, and Frijda were forced to ‘suspend’ their professorships. To fellow German psychologists who had escaped to the U.S. in time, Selz wrote that he hoped “to be considered for future invitations from America to foreign psychologists, even if it may be only for a very modest position”. But his compatriots failed to secure him a position. They still tried to enroll him in a scholarship program, but Selz appeared to have passed the age limit for the program. Thus he remained in exile in Amsterdam while the net closed around the Jewish community.

Step by step, the rights of the Jews were further restricted, and many lost their employment. From early 1942 onward, unemployed Jewish men and boys were drafted for “labor” in Westerbork. Westerbork, established in 1938 after the Kristallnacht as a reception camp for refugees from German refugees, had been transformed by the German occupiers into a temporary transit camp for Jews and other prisoners to be deported. Herman Frijda, like many other Jews in the Netherlands, went underground to escape the raids.

Selz estimated that his war medal would protect him, but despite Révĕsz’s petitions to the Central Bureau for Jewish Emigrants, he was arrested in July 1943 and sent to Westerbork; no Iron Cross could help it. From there he sent a postcard to Amsterdam: he intended to hold a series of lectures for the benefit of the residents. It would be his last sign of life. On Tuesday 24 August 1943 he was put on a transport to Auschwitz by train no. DA 703.

Of the entire generation of great German professors – the famous Gestalt psychologists – Otto Selz was, as far as is known, the only one whose life ended in the Nazi camps. His death is recorded on August 27, in or near Auschwitz. He died immediately upon arrival in the gas chambers. Or perhaps he already died of exhaustion or suffocation during transport. Or he was killed during an escape attempt, or a staged escape. We will never know.

In 1944, Herman Frijda and two sisters of Philip Kohnstamm also died in Auschwitz. More than 100,000 Dutch Jews, and some 15,000 Jewish refugees from Germany, were put on transport via Westerbork and murdered in the concentration camps. The bricks in the Names Monument are the silent witnesses.

Adriaan de Groot and Nico Frijda have not been forgotten; their work brought them fame and acclaim.

Otto Selz awaited oblivion, despite his groundbreaking work. There’s no fairness in that.

Otto Selz’ legacy

“Selz probably found the most recognition, and at least some personal friendship and warmth, in the Netherlands. This thought can be a comfort to us when we think of the tragic end of his life.” These were the words that concluded the obituary for Otto Selz written in 1946 by Selz’s most important Dutch student, Adriaan Dingeman de Groot.

In his experimental research into chess thinking, De Groot made fruitful use of Selz’s advice, and applied his self-report method to chess. His main work, Het denken van den schaker, was published in 1946. The English translation from 1965 (Thought and Choice in Chess) still is by far the most widely cited scientific work on chess thinking.

The introduction of the first computers in the late 1960s was crucial in establishing cognitive psychology, and in spawning the subsequent cognitive revolution. It stimulated Herbert Simon, who later became the first psychologist to receive the Nobel Prize, to design software that mimicked human problem-solving.

Selz’s mechanistic schemes of thought proved to be directly applicable to this end; in essence, he was a pioneer of artificial intelligence, as is so dominant today. As the celebrated ‘father of the cognitive revolution’, Herbert Simon acknowledged his extraordinary debt to Selz’s ideas, which he had borrowed from De Groot’s dissertation. (Simon learned Dutch especially so as to be able to read De Groot’s book, even before it came out in translation.)

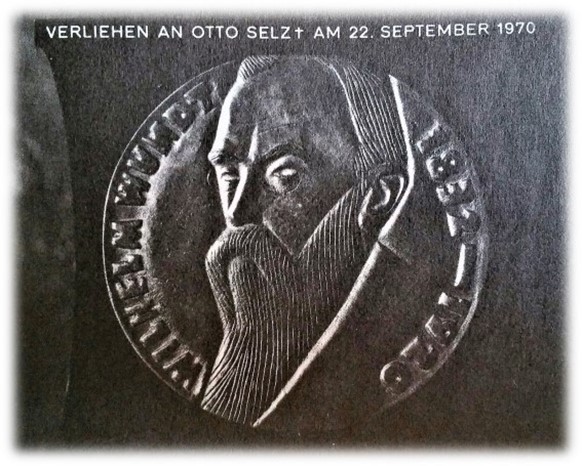

Shortly thereafter, recognition for Selz, and for the injustice done to him, would also arise in Germany. In September 1970, the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychologie posthumously awarded Otto Selz its highest award: the Wilhelm Wundt Plakette, for his eminent achievements in psychology. The plaque was received by the Psychological Laboratory of the University of Amsterdam, where the bronze insignia was put on display.

This recognition and the efforts of Frijda, De Groot and other Dutch and German scholars notwithstanding, Selz’s teachings and his pioneering role have since been all but forgotten.

Remembrance

In 1982, I started my studies at that same Psychological Laboratory, and from that period I have vague recollections of the Wilhelm Wundt Plakette on display in the main hall, somewhere halfway between the glass reception and the orange elevator doors. Psychology moved to another building in 1990, and again in 2011, and again in 2015; and at some point the plaque was lost.

It was a round, bronze insignia of about 20 centimeters in diameter, Nico Frijda remembered in 2015 (in retrospect, shortly before his death). An extensive search revealed that during the last move, when everyone was encouraged to dispose of superfluous clutter, an industrious official had deposited the plaque in a dumpster. It was only by accident that a passerby who noticed the incident subjected the heavy object to closer inspection with a passing professor. In doing so, they saved the plaque from destruction – the fate that Selz himself had suffered.

On April 21, 2022, Selz’s Wilhelm Wundt Plakette was ceremonially reinstated in the central hallway of the Psychological Laboratory of the Universiteit van Amsterdam. May the plaque dedicated to him, like his brick in the wall, revive the memory and appreciation for Otto Selz, a forgotten pioneer.

Selz had been a member of the Gesellschaft from 1913 until his death.

(photograph by the author)